P-Behavioural Finance

Behavioural Finance

It is very easy to use behavioural finance as an interesting source of anecdotes and stories about how we’re all ‘irrational’ in amusing ways. This white paper outlines how we at wealth management company have used this knowledge to create practical investing applications.

Investors deviate from good investing practice because good long-term investment decisions are invariably uncomfortable along the way. Our behavioural finance approach is not to ignore this human need for comfort, but to acknowledge it and ensure that we can help each of our clients achieve it as efficiently as possible.

Only by having a practical system that addresses their needs for emotional comfort along the journey will investors be able to endure the ride, and get to the end with the sort of returns they should.

Our interest in behavioural finance

Our investment began with the creation of a dedicated team of behavioural finance specialists, with academic expertise spanning decision science, quantitative finance, behavioural psychology, and experimental economics

Their remit was twofold:

first, to draw on their expertise and academic knowledge to improve our understanding of how investors make decisions; and

second, to design practical systems to help us – and our clients – improve investment decision making.

Over the years, we have blended this knowledge with original research and extensive practical experience advising investors to forge an entirely new way of bringing behavioural and classical finance together into a single coordinated framework that enables us to:

Understand how and where individual investors face the greatest headwinds to achieving their financial goals, and offer a range of highly practical, and individually targeted, advice for making them sufficiently comfortable with their portfolios to help overcome investing mistakes.

It is very easy to use behavioural finance as an interesting source of anecdotes and stories about how we’re all ‘irrational’ in amusing ways. This white paper outlines how we at Barclays have used this knowledge to create practical investing applications.

“We are constantly reminded that individuals consistently struggle to get the sort of investment returns they should”

Our enhanced approach

Our analysis has led us to fundamentally challenge the traditional idea that investors want the best risk-adjusted returns. This notion assumes that investors are concerned only with long-term financial efficiency and that they are able to ignore their very real emotions over the investment journey.

Unfortunately, the evidence suggests that the natural behavioural need for emotional comfort across the investing experience costs the average investor around 3% per year in foregone investment return. For some, the cost can be substantially higher. As a result, actual investor returns are improved by focussing instead on achieving the best anxiety-adjusted returns: the best possible returns, relative to the anxiety, discomfort and stress they’re going to have to endure over the volatile investment journey.

Investors deviate from good investing practice because good long-term investment decisions are invariably uncomfortable along the way. Our behavioural finance approach is not to ignore this human need for comfort, but to acknowledge it and ensure that we can help each of our clients achieve it as efficiently as possible. Only by having a practical system that addresses their needs for emotional comfort along the journey will investors be able to endure the ride, and get to the end with the sort of returns they should.

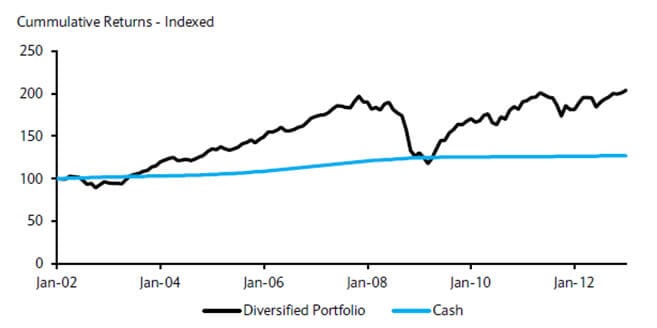

The returns depicted for the hypothetical Diversified Portfolio above do not represent actual portfolios, nor do they reflect trading or the impact of material economic and market factors including fees. Hypothetical illustrations and performance have certain inherent limitations. No representation is being made that any client will or is likely to achieve the hypothetical return represented in the illustration on this page.

It is important to note that the Cass study’s behaviour gap is an average: Some investors did better, but some did worse. For a first-time investor who entered the equity markets in a state of emotionally charged enthusiasm at the peak in November 2007, and later sold in terror at the beginning of March 2009, a mere 1.2% behaviour gap would have been extremely soothing.